When the Etne area became ice-free toward the end of the last Ice Age, the sea level rose to about 70 metres higher than today, since the ice had been pressing down the land. Just below Håfoss, in the blue clay on what earlier had been seafloor, shells have been discovered that lived about 14 000 years ago.

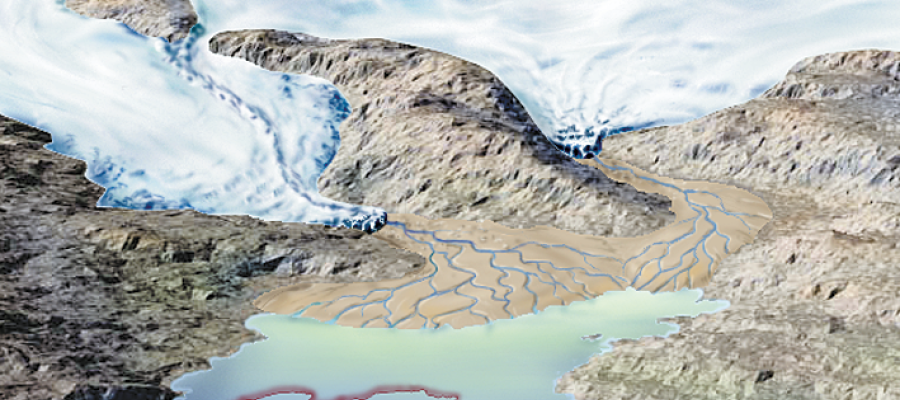

Stordalen was probably ice-free for a while before the glacier arrived at Håfoss. As it proceeded, the meltwater rivers carried large quantities of sand and gravel out into the fjord. The sloping layers (known as forset beds) and top layers (topset beds) that were laid down then, about 13 5000 years ago, and which we can see today in the gravel quarry by Nord River, filled the fjord all the way up to sea level in a big delta in front of the glacier. By this time the sea level had risen several more metres and it stood ca. 80 metres higher than today.

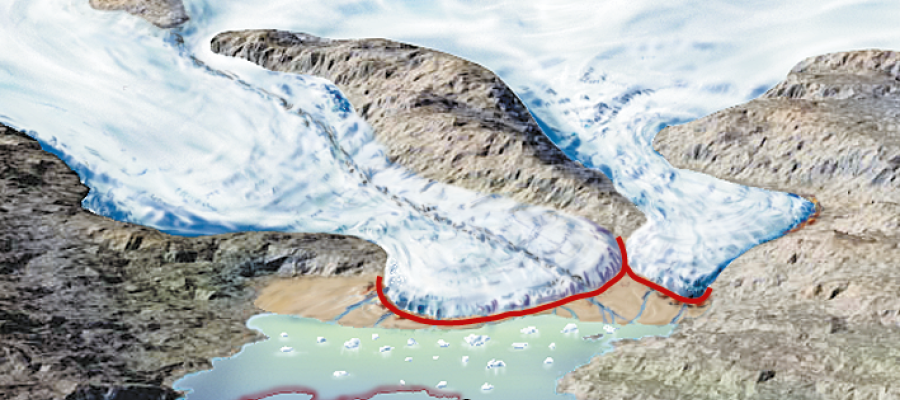

About 1000 years later, during the cold period known as the Younger Dryas, the glacier advanced again both in Stordalen and Litledalen, and spread out over parts of the delta, without the delta sediment being shoved away. The tongues of the glaciers from Stordalen and Litledalen just about reached each other about 12 3000 years ago, and they deposited end moraines in two arcs from Austreim to Steine.

Toward the end of the Younger Dryas the valley glaciers had one final spurt. The side moraines from this last ice advance come into view especially well in the landscape to the north of the agricultural college in Etne.

The climate grew milder about 11 500 years ago, and the glaciers began to melt. During a short period small lakes were formed between the glaciers and the delta flats. Fine-grained sediments were deposited, layered glacial sea sediments, that we now find in Londsalen, between Håfoss and Austreim, as thin layers of alternating silt and sand.

The glaciers then disappeared, and when the weight of the ice was gone, the land rose. The rivers carved down through the large terraces and transported sediments to ever lower delta flats out in the fjord.

Eventually, large river plains were formed by the meandering rivers that continually carved new channels as they simultaneously deposited sand and gravel on their journey to the sea.