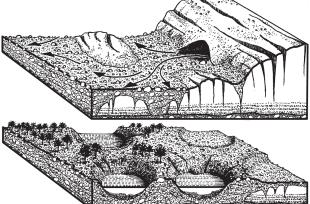

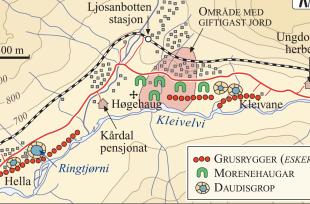

In the flat valley bottom around the Kårdal boarding house, the last remaining ice melted from the glacier between 10,500 and 11,000 years ago. While the glacier still covered the valley, the meltwater flowed in a tunnel under the ice. Sand and gravel were deposited in the tunnel. When the ice disappeared, the tunnel deposits were left behind as gravel ridges. The ridges are still clearly visible in the terrain, many thousands of years after they were formed.

There were also large partially-buried ice blocks under the moraine deposits when the ice melted away from the surface. After a time, these blocks melted, the deposits sunk together, and where the ice blocks had been, depressions were formed in the terrain. With time these depressions get filled in with precipitation and water seepage, to become large ponds and small tarns. Geologists call such holes "kettle holes". Some of the depressions are tarns also today, while others have grown in with vegetation.

Anorthosite

The place and the mountain are called Mjølfjell - it is the bedrock, the white anorthosite, which has given it its name. The rock is made up almost exclusively of one mineral - feldspar. Feldspar contains large amounts (30%) of aluminium dioxide (Al2O3), a chemical that is toxic - for plants. Not only is the ground toxic, but the earth is also depleted of important trace elements, such as phosphorus and potassium. The vegetation here is therefore sparse -and just east of the TV-mast at Høgehaug it is especially barren. With little vegetation to bind the soil the frost action gets easy access. Repeated freezing and thawing turns and sorts the soil and stones in the flat part. On the slopes with loose deposits of anorthosite, the earth sinks - the sparse vegetation is not able to hold it in place. The new cabin area at Mjølfjell lies between 650 and 700 m a.s.l. The special conditions in the soil make the nature in this area more exposed and vulnerable than in many places higher up in the mountains.