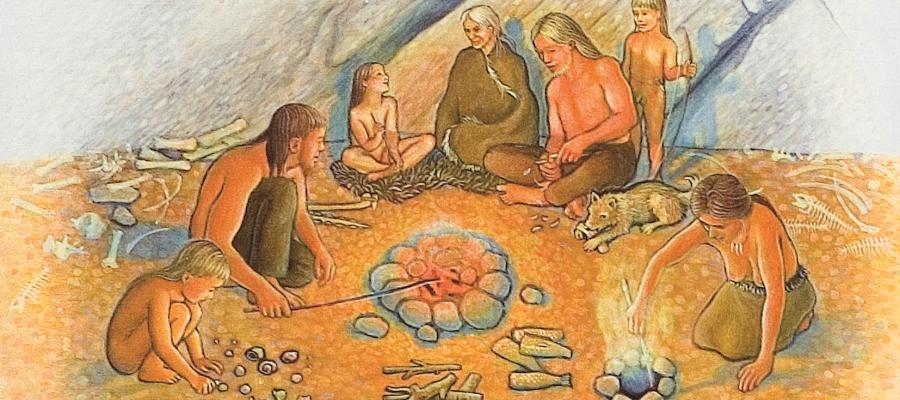

Roughly 7000 years ago Strauma was one of the best - if not the best - hunting spot in all of Hordaland. It is doubtful that the Stone Age peoples who settled at Skipshelleren realized just how lucky they were. In the piles that archaeologists dug in 1931-1932, one could find scraps from hunting and cooking, bone and horn, guts and shells, tools and stone slabs. From this material it has been possible to piece together what life was like here by the river.

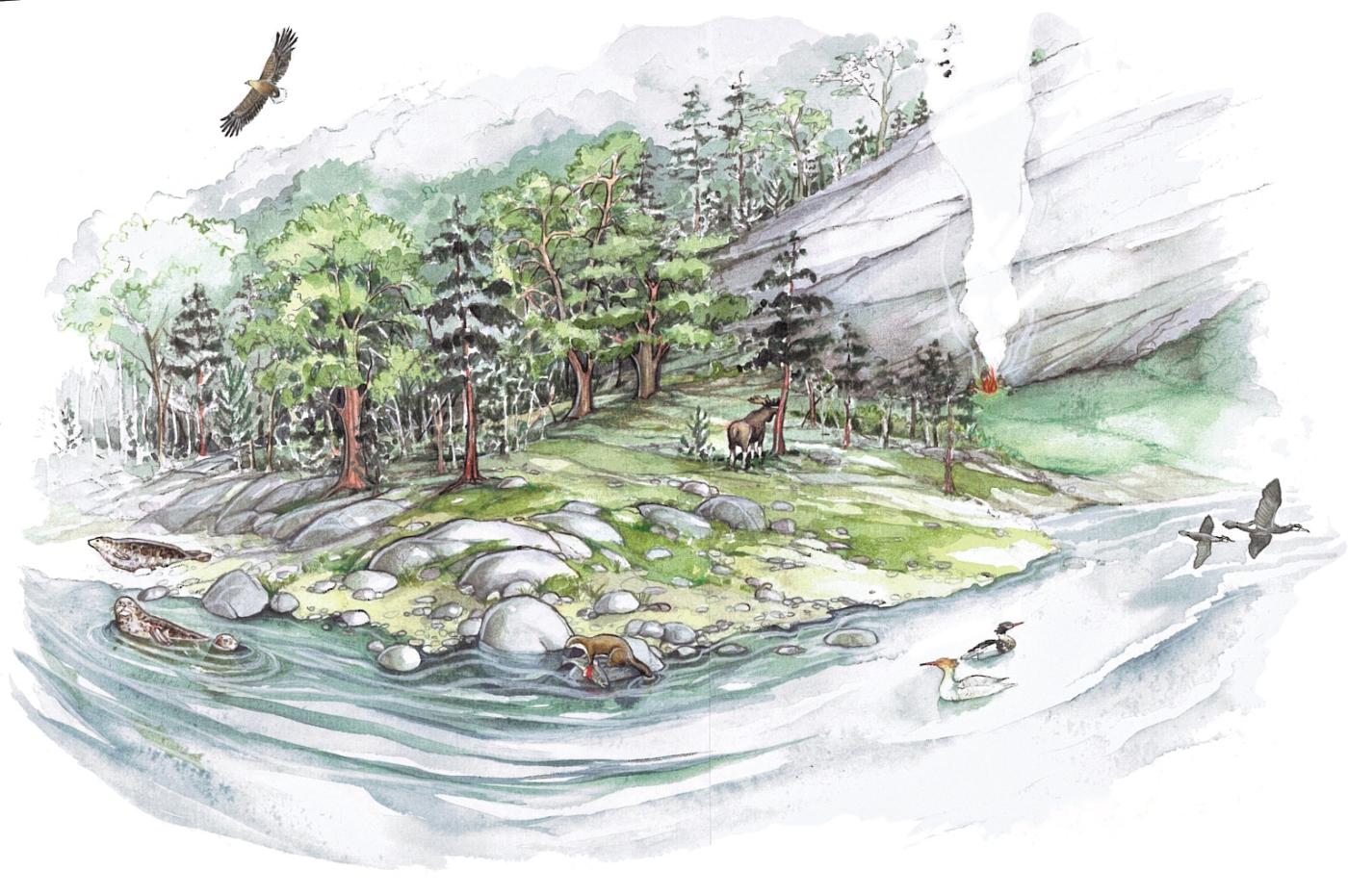

The amount of game was much greater in the Stone Age than now, but many of the species that were hunted are still to be found at Straume. The abundance of salmon was one of the most important reasons why nature's larder was so well-filled just here. All of the salmon that travelled to Vosso had to pass Straume, and the passage was so narrow and so shallow that the fish could be caught by simple means - also by hunters other than the two-legged. Where the salmon led, the harbour seal followed. If the Stone Age humans got tired of salmon, they could just change the menu to harbour seal. An adult harbour seal can weigh about 100 kg, enough for a feast for a whole clan for several days. It was nonetheless mostly young seals that were caught. This suggests that the harbour seals bore their young on the beach at Skipshelleren.

The remains of 48 bird species have been found in the bone material. The fish-eating Red-breasted Merganser must have had extremely good feeding conditions at the outflow of a river as big as the Vosso. For the Red-breasted Merganser the smolt making its way out to the sea was important. Many other smaller types of fish also found good feeding grounds in this shallow brackish water area with its strong current. The Red-breasted Merganser is found at Strauma today, but not in as large numbers as in the Stone Age.

Stone Age folk ate a lot of saltwater fish, and the bone discoveries suggest that these were the same types as are found in Veafjord today. Saithe, cod, pollack, ling and haddock. Bigger changes have been observed, however, among the mammals on land. Deer steak was popular then as now, and a whole 69% of the bone remains from the game meat came from the red deer. The people who lived here could eat as much meat and fish as they pleased, split the long bones with precision to obtain bone marrow, break jaw bones for the sweet tooth nerve and they probably drank the blood while it was warm and steamy. There has not always been a lot of red deer in these parts. Early in the 1900s the red deer population in Hordaland was very low, and there may have been many such periods over the years.

It is not known how they hunted bear, but it was probably seen as a dangerous pastime. At Skipshelleren they could nonetheless feel quite secure when they went to sleep. At that time the sea level was 13-14 metres higher than now, and then there was only one passage that had to be guarded against unwanted intruders.

A couple of thousand years later people from a nascent agricultural society were the ones to inhabit the cave. Bones from sheep, goat and cow show that they kept domestic cattle, but judging from the finds, hunting and fishing were equally important.After this the cave was in use, both in late Bronze Age and through early and late Iron Age. Finds from all these periods were excavated, layer upon layer in the refuse tip. Here were tools of several kinds and remains of weapons, cooking vessels and decorative items.

In later centuries – perhaps from the Middle Ages – the cave has served as storage place for boats and ships during the winter, and this is how it has acquired its name, the last of many. But what the people who lived in this cave have called this ancient place – from the deer hunters in early Stone Age to the Iron Age farmers – is lost forever.