It is not only the U-shape that is the trademark of glacially-carved valleys. Side valleys often run much higher up than the main valley, appearing as "hanging valleys". A profile along the length of the valley is stair-shaped, with troughs and thresholds. The troughs may be small lakes or become filled with sediment, now forming flood plains. The thresholds create waterfalls or rapids where the river cascades downward (the word "eksa" suggests "gets thrown outwards").

Eksingedalen has all of these characteristics of a glacially carved valley. Since the rivers in Eksingedalen today carry little sand or gravel, one may ask how the floodplains further up in the valley were formed.

To find the answer, one must go back to the end of the last Ice Age. Before the floodplains in Eksingedalen were formed, the glacier calved into the fjord, then it stopped first at Nordheim where the sea was about 60 metres higher than today, and then a bit later at Eikefet. The terrace at Eidslandet was deposited at this time. These sandy deposits have been quarried for sand over many years, so large portions of the terrace have been removed. The sand quarrying today has been moved to Eikefet.

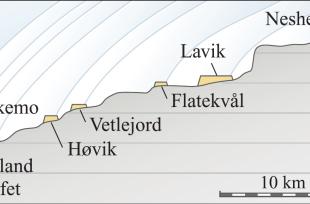

When the glacier melted back further up the valley, it stopped sometimes for short intervals. At each stop large quantities of sand and gravel were deposited in shallow rivers ahead of the glacier. The rivers built up large flood plains, or outwash plains, as geologists call them. The result can be seen as large, even plains with loose sediment deposits at Løland, Eikemo, Høvik, Vetlejord, Flagekvål, Lavik and Nesheim.

The largest floodplain lies at Lavik. It is 2.5 km long and 150 m wide, and was deposited when the ice front lay at the mouth of the Fagerdalen valley. Just below this there are large boulders at the surface. They bear witness to enormous amounts of water during deposition.