"The Sogn river"

The Sognefjord is the biggest fjord in the west of Norway, and before the ice ages the biggest river flowed westward along the "Sogn valley" where the fjord is now. The river reached the ocean off Solund. In the eastern part of Sogn there were many tributaries that flowed into the main "Sogn river". We can still see traces of these minor rivers in the form of hanging valleys. The tributary flowing where the present eastern Nærøyfjord is located had its sources at the mountain "Skammedalshøgdi", 1600 metres above sea level east of Gudvangen. On the western side of the fjord, the water divide between Sogn and Voss was located in the mountains due west of Bakka (Bakkanosi - Vardafjellet).

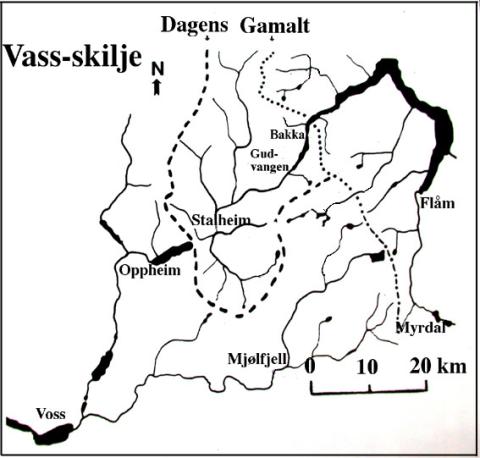

Map showing the old and the new water divides.

The Sognefjord glacier

When the ice ages set in, the glacier in the "Sogn valley" became much bigger than the glacier that followed the Voss valleys. In the course of many ice ages, it therefore eroded more efficiently the Sognefjord to immense depths (the bedrock is up to 1500 metres below sea level in some places). For this reason, the sea eventually filled the Sognefjord basin all the way to Gudvangen, whereas the rivers flowing eastward in the direction of Voss only reached the ocean at Bolstadøyri. In this way, the river of Nærøyelvi got a much steeper fall and eroded more quickly into the bedrock. As rivers erode valleys "backwards", the river of Nærøyelvi "caught up with" one Voss river after the other. These tributaries then had to change direction quickly and flow towards Sogn. A case in point is the foot of the characteristic mountain Jordalsnuten where the river of Jordalselvi makes a sudden turn to the northeast, joining the main river of Nærøyelvi down to the fjord at Gudvangen. The river of Jordalselvi has its source in the Fresvikbre glacier and runs along a long, almost flat valley (Fresvikjordalen) through four municipalities (Vik, Leikanger, Aurland and Voss). Just after the farm Jordalen, the valley narrows and the river cascades in waterfalls and rapids down in the gully that the Norwegian poet Per Sivle used to call "Helvete" (Hell).

Valley ledges reveal old valley floors

Standing on the terrace of Stalheim Hotel we can see valley ledges on either side of the valley of Nærøydalen. To the left is the old crofter's cottage of Nåli. A hiker's trail leads to Nåli from Brekke. On the opposite side of the valley there is another ledge at the same altitude (about 450-500). These ledges are remnants of old valley floors 200 000 years ago. If we link these two ledges together, we get the floor level of the old valley where the river from Jordalen flowed in the direction of the lake of Oppheimsvatnet. The conditions in the valley of Brekkedalen were similar, where the river of Brekkeelvi now cascades down the waterfall of Sivlefossen and down into the valley of Nærøydalen. Further south, the valley of Øvsthusdalen and those in the Brandsetdalen point to the west, whereas the rivers eventually make an abrupt turn and run north to the waterfall of Stalheimsfossen and down into the valley of Nærøydalen.

View from Stalheim Hotel down the valley of Nærøydalen. The river in the valley has eroded backwards and for example "caught" the river of Jordalselvi now flowing down the canyon on this side of the mountain Jordalsnuten. The valley ledges on either side show the level of the valley floor of the old valley.

The Nærøyfjord inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List

If you stand down at Gudvangen admiring the vertical mountainsides with the impressive waterfall of Kjelfossen to the east, you may feel grateful to the Sognefjord glacier and its eroding forces which turned the rivers and contributed significantly to the Nærøyfjord being inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The landscape features in this area are caused by a succession of ice ages and warmer periods in between where rivers eroded narrow canyons when the landscape was not covered with glaciers. However, the glaciers did most of the erosion and lengthened the fjords far into the country.