Not quite Lego blocks

A study of the foundations under older houses in the island communities to the west of the Straumsfjord, will soon show that a great deal of the stone was imported. And since stone in any case had to be transported long distances, it was chosen from places with good building stone.

In the eastern part of the municipality there was very little of good building stone, although there was plenty of pebble. The conglomerate is not stratified and is therefore not suitable for building purposes. In a weather-exposed area, stone barns and stone protection walls on the wind-exposed sides would be welcome. But the conglomerate is lumpy and formless, which made it impossible to lay a wall with, so that the water thrown against it would always leak out. Stone with a good, flat side is hard to find. It is possible to split the conglomerate, but it breaks arbitrarily. Yet, the rugged, richly coloured shape makes such a wall very beautiful, and this stone type is steady in some walls and in road banks.

Stone deposits at the water's edge

Along most sea shores where people live, there is today stone left after cultivation or extension of fields.

They early made a point of using the stone to make suitable landings for the rowboats, often with a small stone wall on one or both sides, to protect against the sea waves. Later generations developed the fisheries and used bigger boats. In the harbour, therefore, foundations were built for sea warehouses, stone jetties, and in the end breakwaters. At some farms every single stone was used for some purpose or other. This stone sat well in anchor ropes and salmon seine cord, but in small rivers and on beaches there were smoother stones for seine and net sinkers.

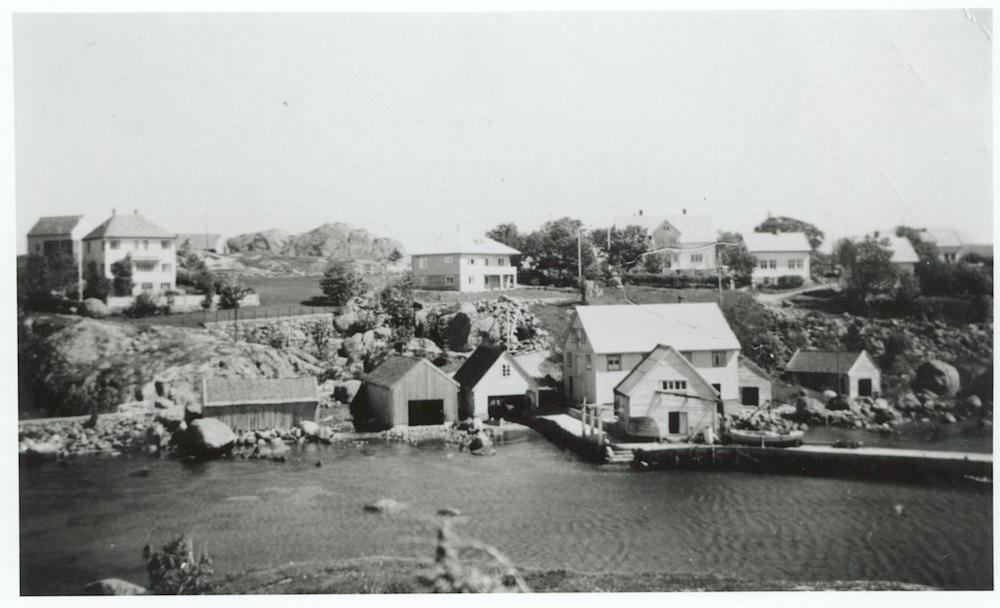

As early as before 1940, Vilhelm T. Færøy was at work on a breakwater, on the west side of Færøy, for protection against the weather-exposed Lågøyfjord. He broke loose great quantities of stone from his fields and took it down to the sea by horse and sledge. Later he removed a huge scree on his property. When his sons were at home from the fisheries, they took their turn in the masonry work and the stone transportation. Year after year Vilhelm worked on this stone project. The picture from around 1950 shows some of the breakwater, all the stone has been cleared from his own farm.

The "stubbebrytar" (tree-stump puller) is introduced

Much of the stone cleared out of the fields was used for foundations under residential houses and barns, and for fences in fields. There were also fishermen farmers who took on cultivation of bog. The stoned ditches they made took the water out of the soil, but could become an abyss for stone when the bog sagged and the ditches clogged.

In the winter of 1909-1910, a youngster from Steinsund went to the agricultural school at Mo. There, he was acquainted with a work-saving wonder on three legs: the "stubbebrytar" (tree-stump puller). He and his brother immediately found fittings and blocks and made the first tree-stump puller in Solund. Others followed when they saw what this equipment could do in terms of cultivation, stone moving, and masonry work.

Stone overhang for shelter

In many places in Solund there are huge rocks that nature has moved and left in such surprising spots that one is tempted to believe they were put there for fun. They have not come a long way, either, since they are of the same rock type as in the rocky ground elsewhere. Strange, perhaps, since this type of rock was melted under high pressure, far under the surface of the earth a long time ago.

When the glacier eroded the north-south mountain ranges, in particular, it deposited a lot of stone on both sides of the mountains. On snowy days in the winter the wild sheep appreciated all these stone overhangs and stone houses which nature had put at their disposal. They assembled there, and there they were easy to find when the owner made his way to them with the sack of hay. And when heavy rain and thunderstorms descended on them in the summer, many a cow sought shelter there from the worst of the weather.

The breakwater at Færøy was some one hundred metres long, and at the far end covered vessels could dock. To the right in the picture, there is a concrete warehouse and a concrete wall with small windows, where people could take shelter while waiting for vessels to come in. A little side wall was also built there, which gave some shelter for the small, fast motor boats.<br />

In the background, the massive breakwater built by the harbour authority in 1961-1963 can be seen. This gave Færøy a safe harbour, at long last. The materials were blasted out of the conglomerate rock at Færøy, and every stone forms part of a colourful work of art.

Conglomerate for decoration

Many people thought that the colourful stone type could be used to make pretty objects, for use or decoration, and in 1981, Buskøy Steinindustri (stone industry) was established by Harald Bontveit and Herman Færøvik. By and by all the machines needed were brought into the production facilities. The raw materials were found only a few feet away, with drills and dynamite. The products were lamps, table tops, gravestones, etc..

After a ten-year period, production lay prone for some years, until young Einar Bontveit in 2000 took it up again, having first received his master's certificate in the stonework industry. Together with his father, Harald, he now runs the business under the name of Veststein ANS. They produce on request from customers, and are constantly expanding their range of products. Their customers are individuals, companies, and building material businesses.