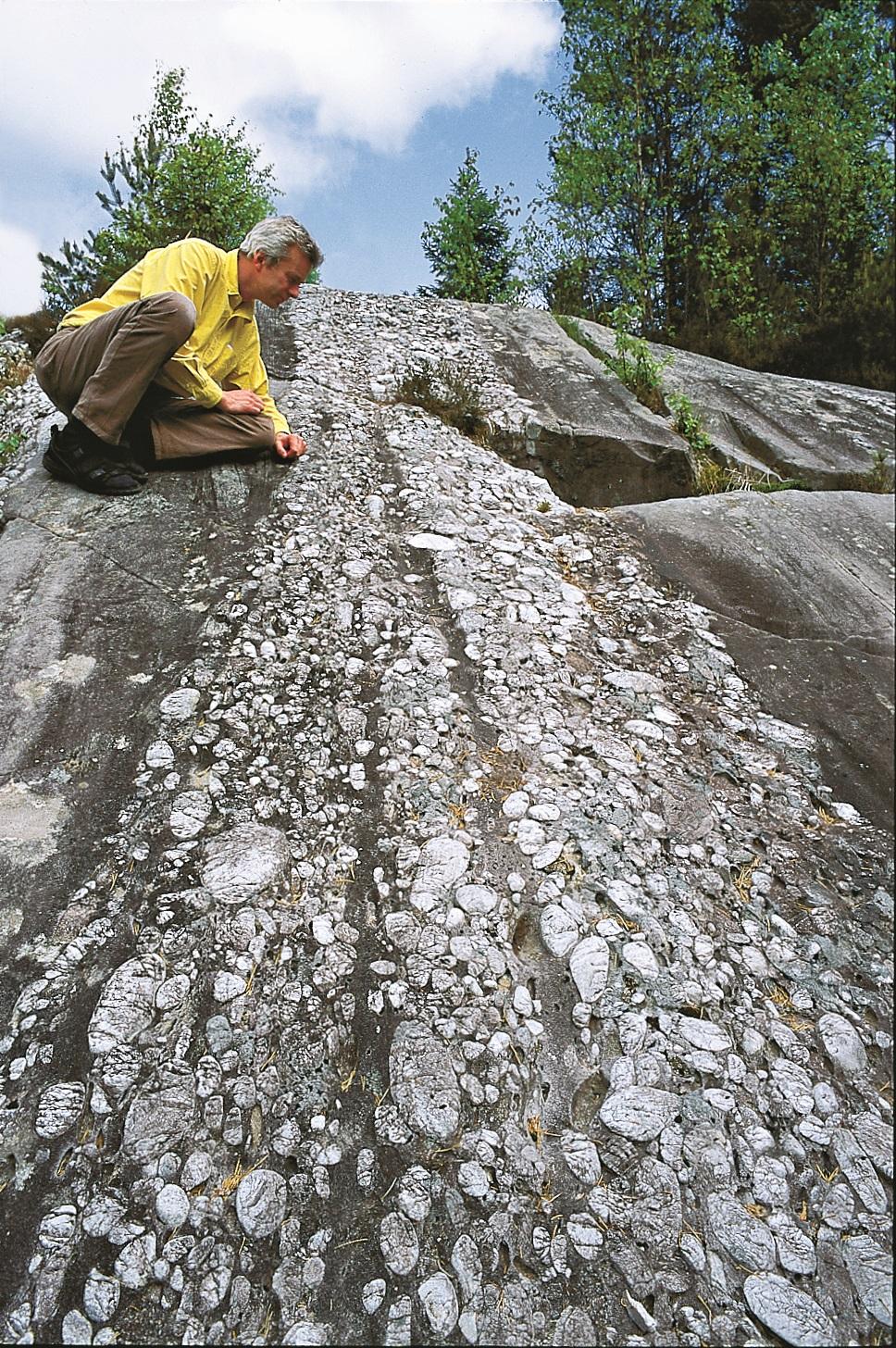

The gabbro and greenstone are related to similar remnants of a nearly 500 million year old oceanic crust in Austevoll and Bømlo. Once, at least 450 million years ago, the oceanic crust got raised up to the surface. First a thin layer of gravel was deposited, then afterwards a thicker layer of clay. Large round quartz pebbles and a thick layer of sand were laid down over that, probably along the coast of what was an ancient sea. Since then these layers have been altered to conglomerate and quartzite, while the lowest layer of clay was altered to phyllite. Finally, molten bedrock penetrated through all these to make veins in the rock layers.

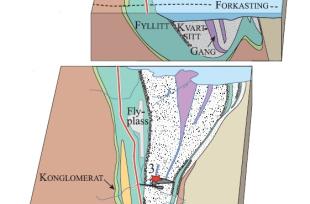

Today some of the rock layers at Ulven are oriented vertically and it is obvious that they once were acted upon by powerful forces that folded them or pressed them down into the earth's crust. Geologists call such folds "synclines". Thrusting of the lowest layers occurred simultaneously with the folding. The folded layers of sand, clay and conglomerate eventually got squeezed into the layers of gabbro and greenstone. This is thought to have occurred during the Silurian Period, in the final collision between Greenland/North America and Scandinavia. This is when the Caledonian Mountain Chain was at its highest.

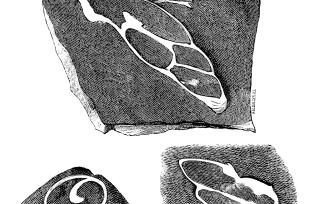

In 1880 Hans Reusch found fossils in the phyllite while he waited for a horse carriage near Ulvenskiftet. Since then remains of both corals, brachiopods and graptolites have been found. Graptolites are a primitive type of colonial animal that lived in the Paleozoic seas. The graptolites in Os are of one type that lived during the Silurian Period about 430 million years ago.

Remarkably, the area around Ulven has been spared much of the deformation that has folded and reshaped most of the rest of the bedrock in western Norway so that it now only remotely resembles its original form. This gentle geological treatment lies behind the discovery of fossils just here, and also explains why the conglomerate is so well preserved.